September is World Alzheimer’s Month, a tradition that began in 2012 to draw attention to this devastating brain disease. It is easy to get discouraged about Alzheimer’s. Worldwide, nearly 44 million people have Alzheimer’s or a related dementia, and the number is expected to increase to 131 million by 2050. The medicines available to treat Alzheimer’s address the symptoms, but as yet the illness has no cure, which is a heart-break for millions of sufferers and people whose loved ones have this disease.

Yet Janssen’s Alzheimer’s researchers remain optimistic. Our scientists and physicians, who are working on new ways to treat and even, perhaps, to prevent dementia, measure their work in terms of progress rather than through the stark lens of success or failure. That is because even when experiments don’t work out as expected, the insights gained can lead to breakthroughs further down the road. So while there is, as of yet, no disease-modifying treatment or cure for Alzheimer’s disease, progress with research gives us reasons for hope.

Here are three:

Upending the status quo: Scientists, physicians and advocates who attended the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in Toronto, Canada, this past summer agreed that business as usual isn’t working. They advocated for changes in the way Alzheimer’s research is conducted; instead of focusing research on people who already have symptoms, they agreed that massive outreach is needed to enroll people who have no signs of Alzheimer’s, but whose brains may already have the conditions that will lead to dementia. Widespread agreement among the Alzheimer’s research community will lead to more long-term studies with healthy people at potential risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. That’s important because….

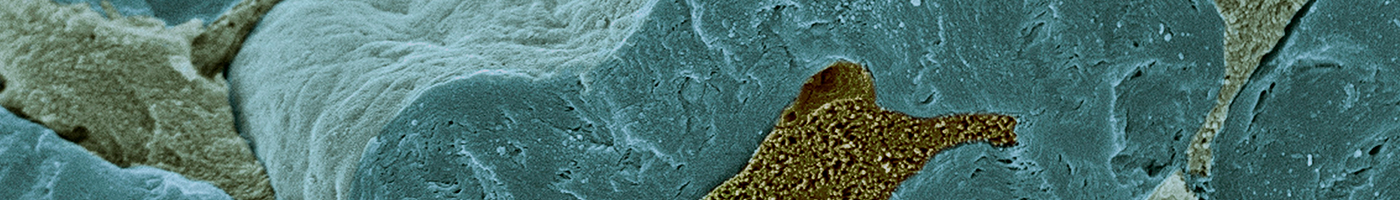

Slowing down decline: This could be crucial to adding a decade or more of healthy life for Alzheimer’s sufferers. Here’s why: When people show signs of dementia, it generally means that a buildup in their brains of beta-amyloid and tau proteins have been destroying neurons for between 10 and 20 years. At that point, valuable time has already been lost. Alzheimer’s is expensive to diagnose properly, too, requiring extensive brain scans. But just suppose you could develop an inexpensive screening test for doctors to track even slight cognitive deterioration for use in an annual physical? With research and new medications, doctors might be able to treat dementia early and slow down the disease, giving people many more years of productive life. With aggressive, early treatment, perhaps a reduced percentage of the millions who are at-risk for Alzheimer’s would develop full-blown symptoms.

That hope is shaping Janssen’s support of a just-launched four-year clinical trial that will track 500 cognitively normal people in London and Edinburgh between the ages of 60 and 85. Half will already have early amyloid accumulations in their brains; the rest will have no detectable levels of the protein. The hope is that the trial will lead to a simple test doctors could use in their own offices so a diagnosis won’t come so late. Meanwhile…

Making progress now: Janssen has taken bold steps with other companies, advocates and governments to begin the process of redesigning the way early scientific research is done in Alzheimer’s. Part of this work involves new financial models to share costs in what’s known as the “precompetitive research space,” or simply to help understand broad scientific principles about the disease or share early data to prevent going down the wrong path, as quickly as possible. Janssen helped found the European Innovative Medicines Initiatives’ EPAD (European Prevention of Alzheimer’s Dementia Consortium), which is pioneering a novel, more flexible approach to clinical trials of new medicines designed to prevent Alzheimer’s dementia. Using an “adaptive” or flexible trial designs, EPAD projects should help to deliver better results faster and at lower costs.

Janssen also is working with the Global CEO Initiative on Alzheimer’s Disease’s GAP Project (Global Alzheimer’s Platform) to establish a standing trial-ready platform, projected to reduce clinical testing cycle times by two years or more and achieve greater efficiency and uniformity in trial populations. The project includes development of certified clinical trial sites and an adaptive proof of concept trial mechanism. This platform will enable delivery of efficient and effective proof of concept and confirmatory clinical trials, and, ultimately, more rapid delivery of effective therapies to patients or those at risk.

Ongoing Clinical Research As far as our own efforts, Janssen has one of the strongest Alzheimer’s research programs in the industry, with projects focused on underlying causes of the illness as well as on ways to slow – and maybe prevent -- disease progression. Our projects include oral medicines, antibodies or injectable medicines, and therapeutic vaccines. One exciting Janssen project is a Phase Two/ Phase Three clinical study of an experimental medicine called a BACE inhibitor which might prevent development and deposits of amyloid, a type of protein, in the brain.

So while this month we must honor and cherish those who suffer from Alzheimer’s and do everything possible to get them comprehensive care they need now, we also must continue to be hopeful about the future. That means working even harder toward the goal of reducing the incidence of Alzheimer’s and, eventually, defeating this heart-wrenching disease through more collaboration and sharing and smarter ways to conduct clinical research.