How can tomorrow’s advances in treating chronic lymphocytic leukaemia help address today’s unmet needs?

Tomorrow marks the start of Blood Cancer Awareness Month and the third annual World Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia (CLL) Day. There is no better time to reflect on the progress that’s been made in CLL, one of the most common leukaemias in the world, and look to the future of CLL therapy.

Over the last decade, we’ve seen a shift from chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) as standard of care for CLL, to oral agents and combination therapies.[1],[2] Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) and B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) inhibitors have offered impressive improvements in overall survival and life expectancy and are better tolerated than CIT options.[3],[4],[5] Risk factor testing is now a reality to identify patients who can benefit the most from novel agents.[6] There’s a lot of progress to celebrate, and a lot still to do.

More advancements, more considerations.

Cancer Immunology is a fast-moving field and, in 2021, Professor Carol Moreno addressed how best to navigate the rapidly evolving CLL treatment landscape. Two years on, I wanted to pause to reflect on what may have changed and consider the unmet needs we continue to face.

CLL is still considered to be the most common adult leukaemia in the Western World,[1] and it remains incurable.[7] While novel CLL therapies have been game changers over the last decade, many patients can present with relapse due to resistance to these treatments, so innovation is still needed.[5] Our overwhelming ambition must be to address this, by continuing to improve patients’ survival and drive towards functional cure.*

We should also ensure we approach treatment in an increasingly individualised manner, optimising risk factor testing to help better predict patient outcomes and guide treatment decisions – let’s consider this for a moment and remind ourselves of the CLL-International Prognostic Index (CLL-IPI). By studying around 28 prognostic variables among roughly 3,400 patients treated in clinical trials, the CLL-IPI revealed the five factors associated with overall survival were: age, Rai stage I-IV, serum beta-2 microglobulin, unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IGHV) genes, and del17p by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or TP53 mutation.[8] TP53 status is one of the most important prognostic and predictive biomarkers in CLL. It should be tested for using a CLL FISH panel, looking for evidence of del17p13 and Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing (NGS) to find TP53 mutations. Both tests are needed as ~3–5% of patients will harbour a deleterious TP53 mutation on DNA sequencing in the absence of del17p13 on CLL FISH, with these patients’ facing poorer outcomes.[8]

Despite the prognostic power this testing provides, it’s not yet standard clinical practice.[9] This is crucial to address as testing allows healthcare professionals to optimise treatment choices, to better suit a patient’s individual needs.

Treatment that’s individualised and considers patient characteristics preferences.

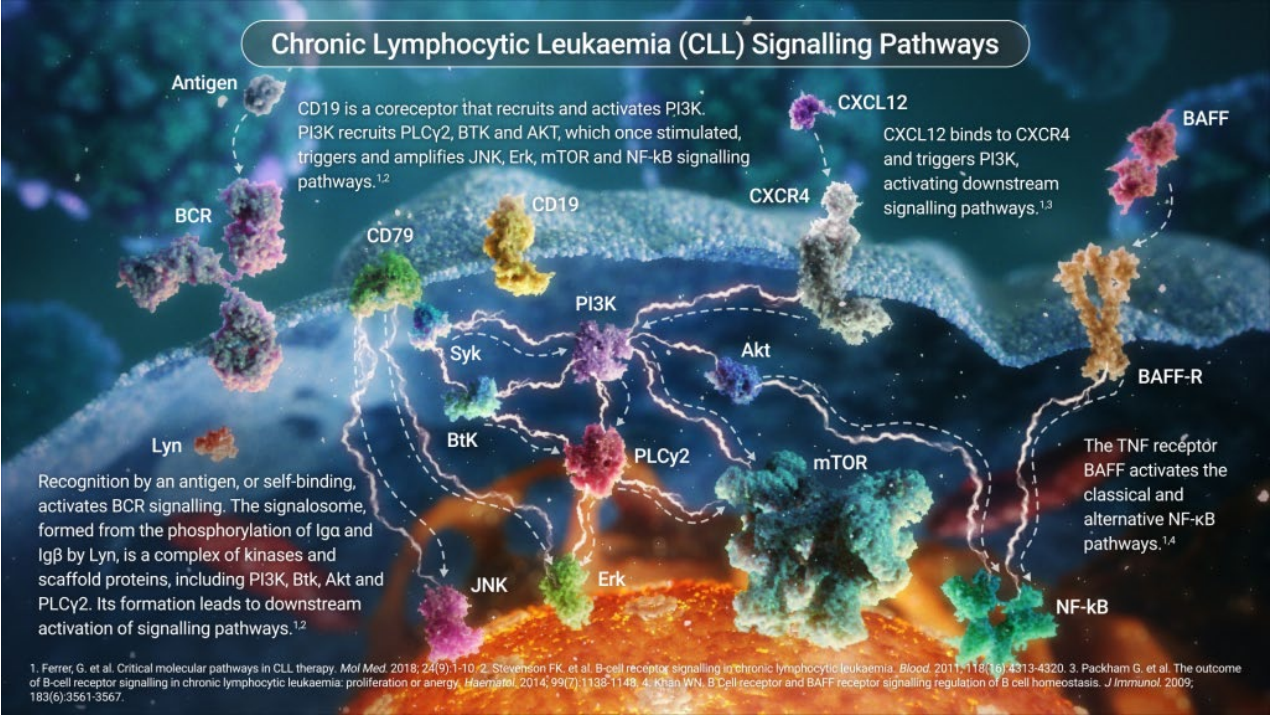

Optimising treatment to address individual needs is an area that I believe will become even more important moving forward. This is because CLL is a complex, highly heterogeneous disease – marked by hypermutations of the IGHV genes, genomic aberrations, and recurrent gene mutations associated with the clinical journey.[1] Given this complexity, the mechanisms underlying CLL pathogenesis have, so far, been hard to fully resolve.[1],[5] But, the more we understand the biology of CLL, the more we recognise the need for different, targeted therapies.[1] Looking ahead, we must continue to discover more about the mechanism of disease, and pay close attention to treatment decisions, patterns and outcomes so we can better serve highly individual patient populations.

Resistance to current treatment approaches is emerging, so we need to consider time-limited combinations and base more treatment decisions on response rates and long periods of remission.[8] We need to compare treatment sequences, combinations and discontinuation. We also need to remember that we’re still in the experimental phase of some of these decisions and we require more clinical data before widespread application in general practice. Techniques like measuring minimal residual disease (MRD) are extremely valuable in this sense, because they allow healthcare professionals to determine the success of cancer treatment at a deeper level – that’s why it’s regularly associated with depth of response and is now a focus of outcomes in CLL clinical trials.[10]

Comorbidities, disease characteristics and prior therapies (where relevant) are all vital when considering a course of action for each patient. The other aspect is, of course, patient preference.[8]

Patients have different experiences and perspectives when it comes to treatment, and it should not be assumed that all patients want the same thing. For example, patients who give a higher weight to severe treatment toxicity can be younger, working and looking after dependent family members.[11] Many cancers have different treatment options at different disease stages, multiple treatment combinations and forms of administration, so patient elicitation is important as these choices can have a huge impact on the patient’s survival and quality of life.

For CLL, as we continue to advance the science, a question may be do patients want fixed-duration combination therapy or suitable continuous single-agent?[7] We know treatment-free intervals can positively impact a patient’s quality of life and functional status, and this may be particularly appropriate and appealing for younger, fitter patients. Given patient choice will often include considerations of lifestyle and emotional impact, and this can then affect the depth of response, we can see why patient discussion plays such a vital role. Patient-centred, individualised treatment options are crucial for CLL therapy moving forward, as well as open dialogue between physicians and patients to explain the various options and actively involve patients at every stage of the decision-making process.

The next frontier in CLL treatment.

Considering these needs and factors, what’s next as we continue to work towards a functional* or even definitive cure?

When it comes to cancer, remission and relapse, we aim for the cancer to not return for years or decades if we’re going to consider treatment a success. Novel therapies and combinations, sequential treatment and discontinuations are all important as we advance CLL care. However, more options can mean complex decision making for physicians and patients, and so getting the balance right becomes important – in other words providing the right therapy, to the right patient, at the right time and considering how to use treatments effectively to avoid resistance.[5]

We’ve touched on significance of measuring MRD, and I do believe the MRD negative complete response is another important cornerstone as we move towards functional or even definitive cure.[8] MRD at the end of CLL therapy, or used dynamically, can be impactful in the era of novel agents where a negative MRD response is a really useful predictor of relapse.[5] It can be a powerful prognostic tool, particularly with time-limited fixed-duration approaches as we may be able to achieve a higher proportion of MRD negative complete responses, which is vital to allow informed decisions about shortening duration of therapy.[5],[8]

Another powerful tool of the future is cellular immunotherapy, and especially the use of chimeric antigen receptor t-cell (CAR-T) therapies, which are already revolutionising other areas of oncology.[12] We have the privilege of knowing that CAR-T therapy has already delivered long term remission for cancer patients, such as Emily Whitehead who, in 2022, celebrated 10 years cancer free after being the first child to receive CAR-T therapy in the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.[13] In CLL, we know CD-19 – expressed on B-lineage cells – is already a key and promising target and CAR-Ts against other, novel, proteins expressed by CLL cells are also being explored.[1]

As a community, we should be incredibly proud of the progress that has been made in the management of CLL. The fact we’ve seen oral therapies, like BTK inhibitors and BCL-2 inhibitors, dramatically improve outcomes for CLL patients[1] should inspire us to continue to push the boundaries of science and care. But, as we continue marching towards ever more innovative therapies, and – hopefully – functional cure, we should also ensure we always remember the importance of patient preference when it comes to treatment decisions. So, on World CLL Day this year, join us in celebrating our remarkable progress, in embracing the patient voice and in advancing the next frontier of individualised CLL care.

*In this article, Dr Chan refers to “functional cure” in oncology. This can be defined as when the patient is in prolonged remission i.e., the disease is completely controlled without the need for ongoing treatment, and in a way that prevents the cancer from causing any illness, for an extended period of time.[14]

References

[1] Yosifov DY, et al. From biology to therapy: the CLL success story. Hemasphere. 2019;3:e175.

[2] Smolewski P, Robak T. Current treatment of refractory/relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a focus on novel drugs. Acta Hematol. 2021;144(4):365-379.

[3] Woyach JA. Management of relapsed/refractory Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2022 Nov;97(2):S11-S18.

[4] Mato AR, et al. Recognizing Unmet Need in the Era of Targeted Therapy for CLL/SLL: “What’s Past is Prologue” (Shakespeare). Clin Cancer Res. 2022 Feb 15;28(4):603-608.

[5] Scheffold A, Stilgenbauer S. Revolution of chronic lymphocytic leukemia therapy: the chemo-free treatment paradigm. Curr Oncol Rep. 2020;22:16..

[6] Eichhorst B, Robak T, Montserrat E, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:23-33.

[7] Mukkamalla SKR, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Updated 2021 Mar 7. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470433/ Last accessed: July 2023.

[8] Hampel PJ, Parikh SA. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia treatment algorithm 2022 [published correction appears in Blood Cancer J. 2022 Dec 22;12(12):172]. Blood Cancer J. 2022;12(11):161.

[9] Parikh SA, et al. Should IGHV status and FISH testing be performed in all CLL patients at diagnosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood. 2016;127;14.

[10] Wierda WG, Rawstron A, Cymbalista F, et al. Measurable residual disease in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: expert review and consensus recommendations. Leukemia. 2021;35(11):3059-3072.

[11] Myeloma Patients Europe. Patient Preference Research. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/presentation/presentation-patient.... Last accessed: August 2023.

[12] Sterner RC, Sterner RM. CAR-T cell therapy: current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer Journal. 2021;11(69). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-021-00459-7.

[13] Cancer Research Institute. Immunotherapy Patient Stories – Emily Whitehead. Available at: https://www.cancerresearch.org/stories/patients/emily-whitehead. Last accessed: August 2023.

[14] International Myeloma Foundation. Road to the Cure. Available at: https://www.myeloma.org/black-swan-research-initiative/road-cure#:~:text.... Last accessed: August 2023.